Episode 2: Detection of Deception

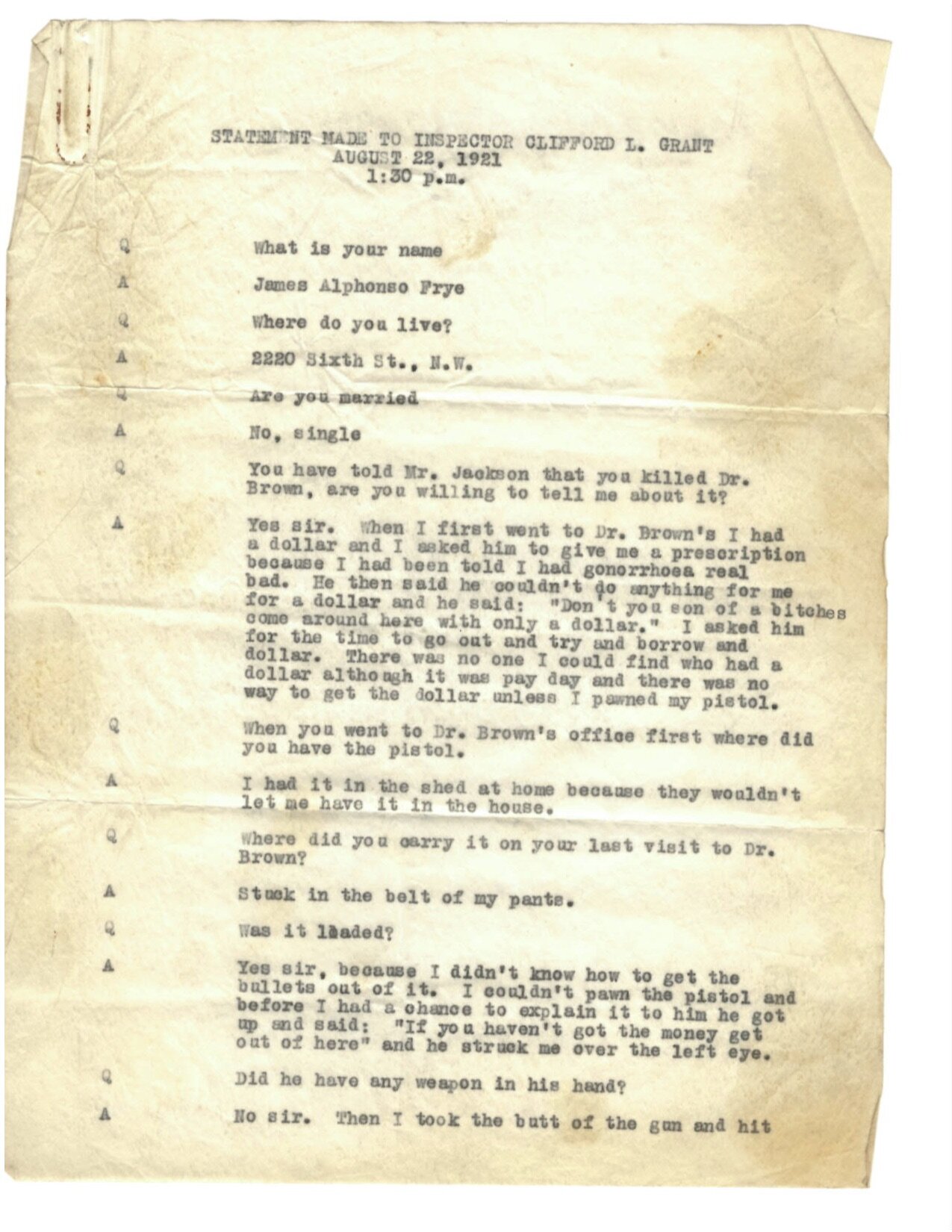

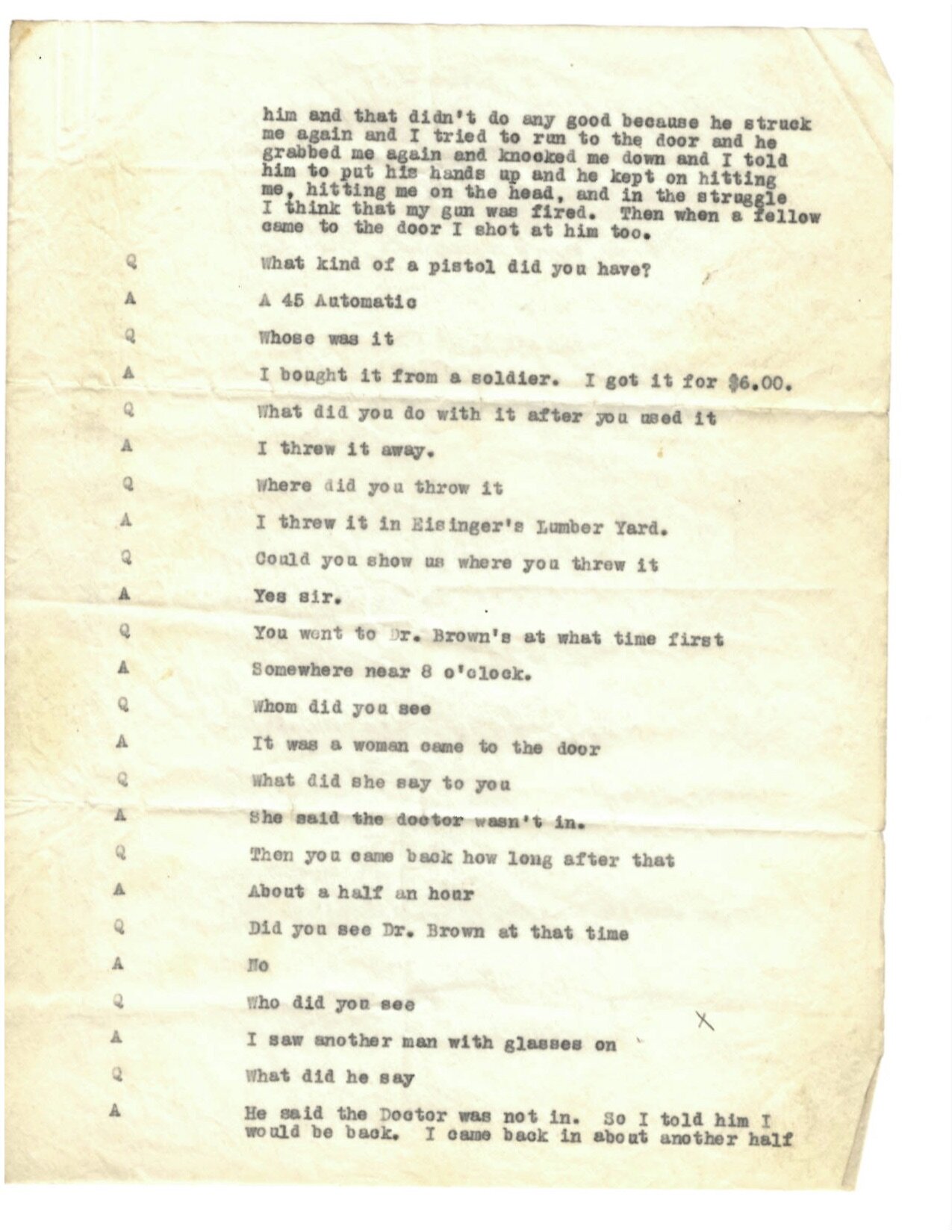

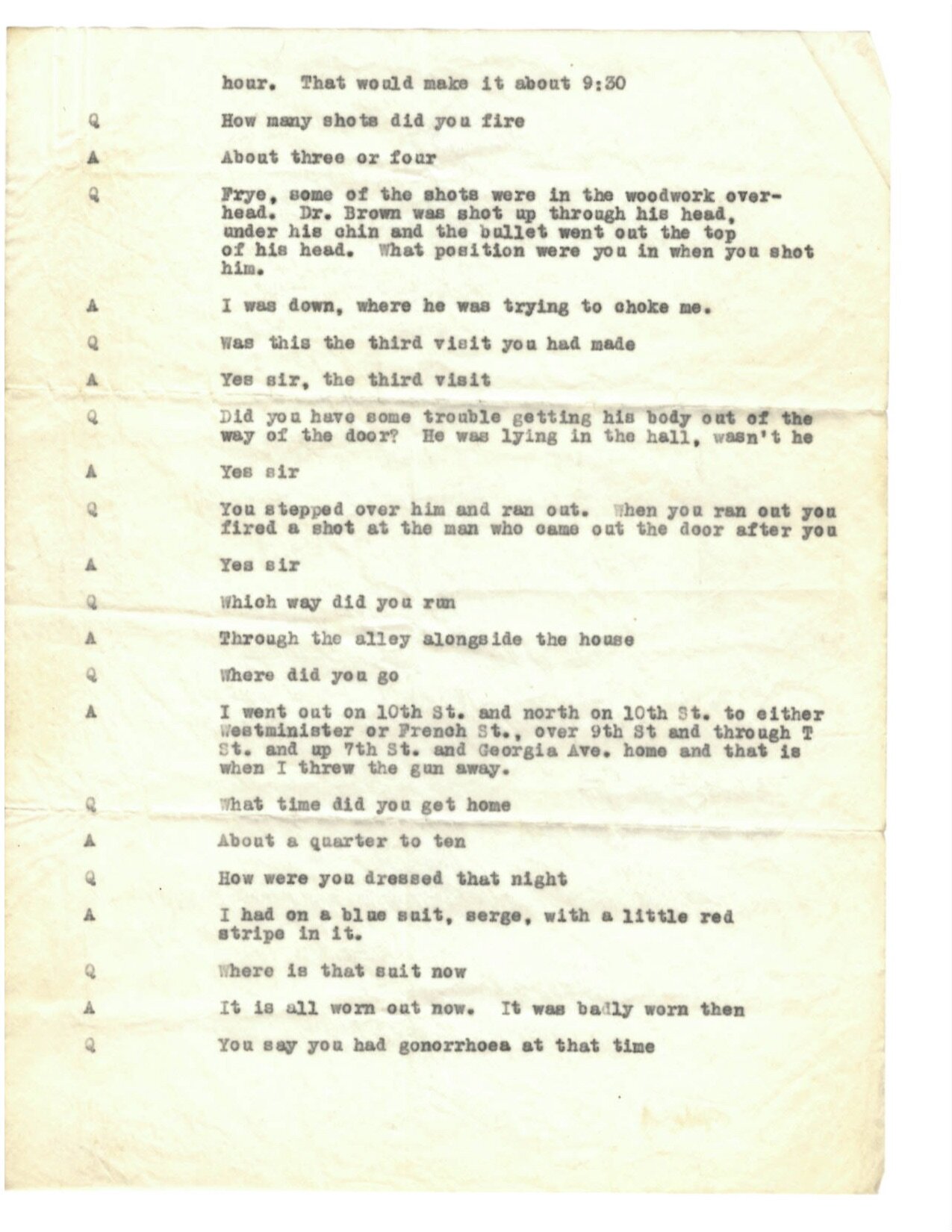

When James Frye, a young black man, is charged with murder…

under unusual circumstances in 1922, he trusts his fate to a strange new machine: The lie detector. Why did the lie detector’s inventor, William Moulton Marston, a psychology professor and lawyer, think a machine could tell if a human being is lying better than a jury? And what does it all have to do with Wonder Woman?

Image: Psychologists and lawyers conducting a lie detector test on James Frye, a murder suspect. (Getty Images)

KEY SOURCES

The full text of Frye’s trial: United States v. Frye, No. 38325 (D.C. 1922).

The full text of Frye’s appeal: Frye v. United States. 293 F. 1013 (D.C.. Cir 1923).

Excerpts from Frye’s applications for pardon. You can find the full letters on file with the National Archives.

William Marston wrote a bunch of papers, including one published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology in 1917 titled, “Systolic blood pressure symptoms of deception.”

The newspaper article “Convict Slayer of Dr. Brown,” Chicago Defender, July 29, 1922.

A newsreel from 1931 in which William Marston uses a polygraph machine to study the difference between blondes, brunettes, and redheads.

An ad for Gillette from 1938 in which Dr. William Marston conducts a lie detector study proving (so he says) that shavers prefer Gillette blades.

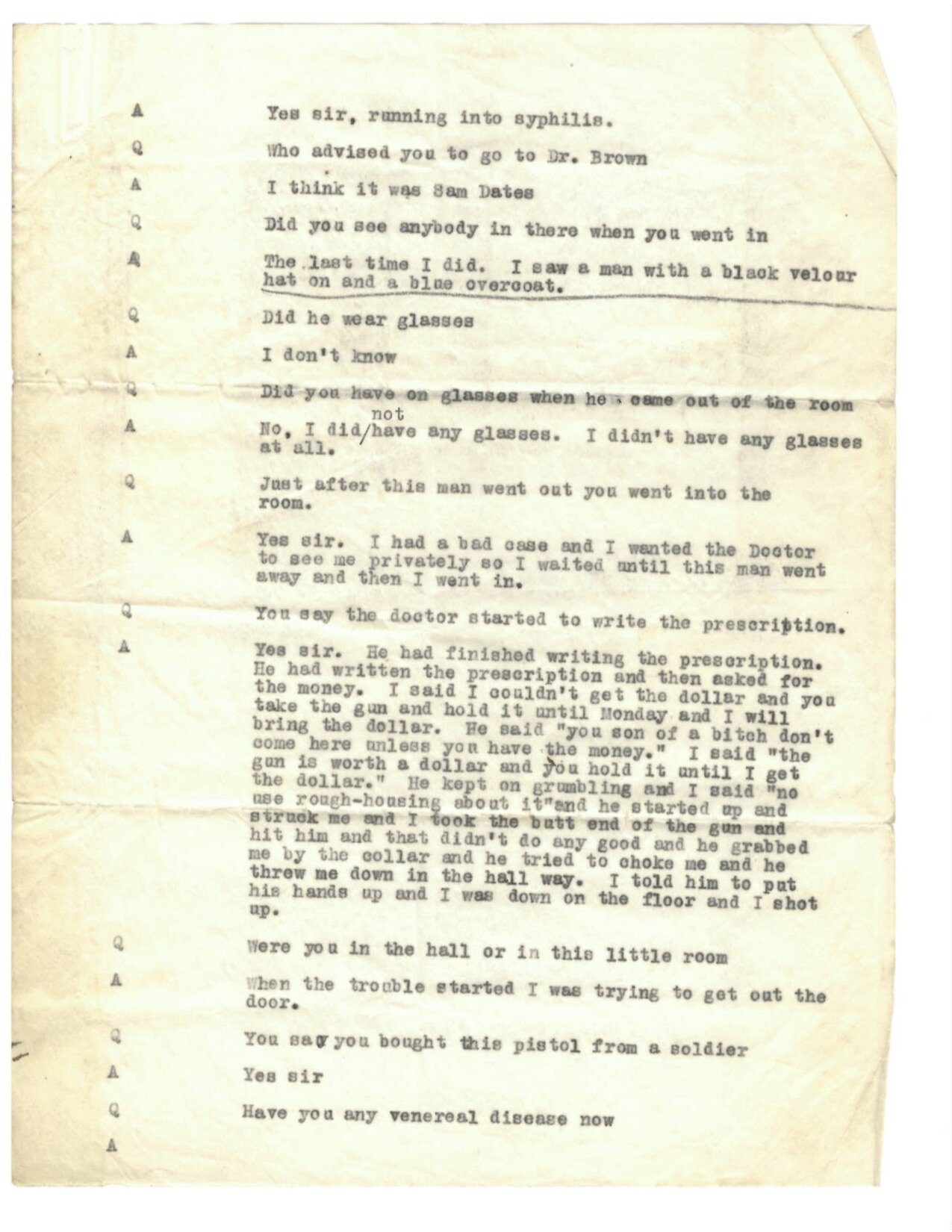

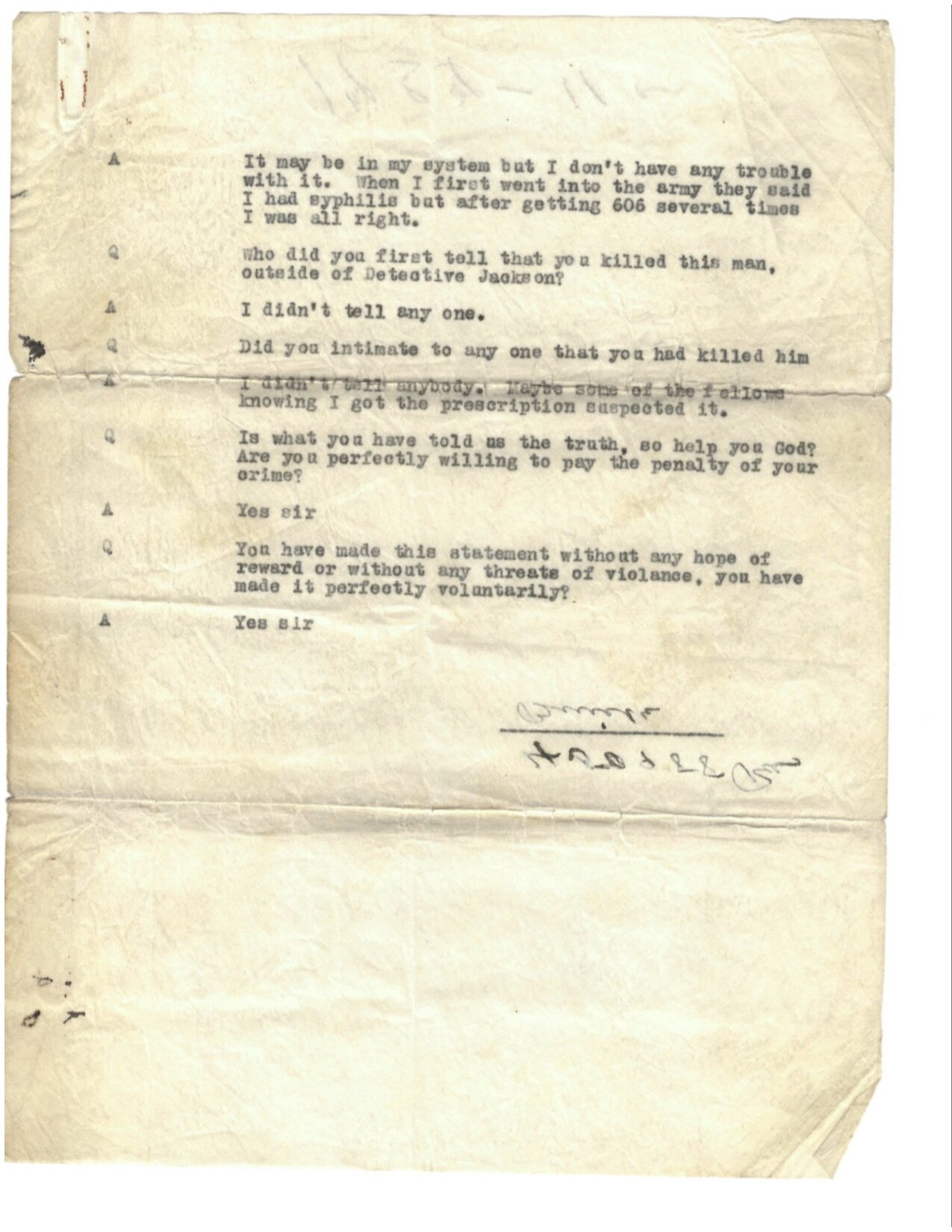

The record of James Frye’s police interrogation. Equity Case No. 40432; “Equity Case Files, 1863–1938,” A1 Entry 69; Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.